“Immutability enables the JavaScript of the future”

I couldn’t agree more. This characteristic, native to functional languages, is gaining major importance, and today we’ll see why.

One of the most important characteristics of functional languages is that their data structures are immutable, which has been shown to reduce software complexity.

Truth is constant change, mutation hides change, change manifests as chaos, therefore, the wise embrace history. — The Dao of Immutability

But in imperative languages like JavaScript, data is mutable by default.

const objeto = {cosa: 'casa'};

function cambiarCosa(obj) {

return obj.cosa = 'Carro';

}

cambiarCosa(objeto) //mutación

console.log(objeto) // {cosa: 'Carro'}This is useful because it’s much easier to model a game character as a mutable object that changes its state, rather than modeling it as an immutable object that creates a new instance of the character with every state change.

The problem is that we have no way of knowing the past state of our character, so we have to take time into account.

Let’s understand how immutability helps with this.

What Makes Us Immutable

An immutable value is one that cannot be changed after being defined. It can be modified, but it must be in a different object.

But this raises a question: isn’t creating a new object for every change expensive? Yes, because it has to be instantiated again in memory.

This has been a subject of research for decades, and today we have quite efficient solutions for creating immutable data structures that give us data persistence and good access performance.

When we create data structures, we mainly care about two things: how the data is stored and how fast we can access our data.

What’s the Goal?

What we’re mainly looking for when storing our data immutably is to have data persistence.

We want to know what has happened with our data over time.

Some types of persistence we can find are:

- Partial persistence: Every version of the data ever created is accessible, and only the latest version can be modified.

- Full persistence: All versions are accessible and modifiable. (default in imperative languages)

- Confluent persistence: Partial persistence + the two latest versions can be combined.

- Functional persistence: No previously created version can be modified. You can only create new versions of the data from existing ones.

Of these, functional persistence is particularly useful to us.

How We Store Our Data

Two of the most important ways to structure our data for functional persistence are Array Mapped Trie and Hash Array Mapped Trie.

As I mentioned, it’s expensive to create a new object every time there’s a change, especially with complex objects. That’s why these data structures work with something really cool: Structural Sharing

Let’s understand this.

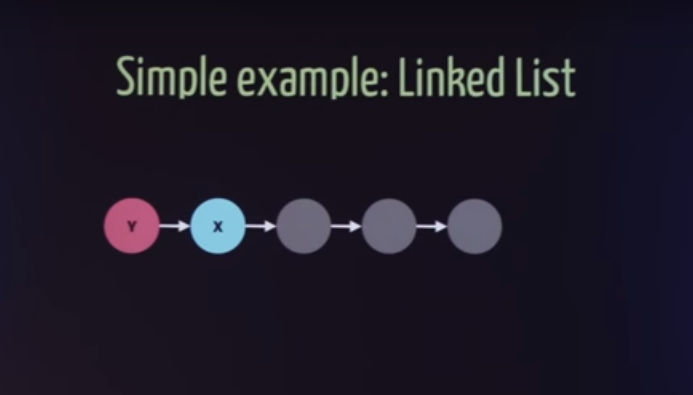

If we have a structure like this, a linked list:

David Nolen — Immutability, interactivity & JavaScript (FutureJS 2014)

David Nolen — Immutability, interactivity & JavaScript (FutureJS 2014)

If I have a version in state x and create a new version with state y, the structure will be shared.

This way, we don’t have to create a new object for every change. We only modify the references that make up the object.

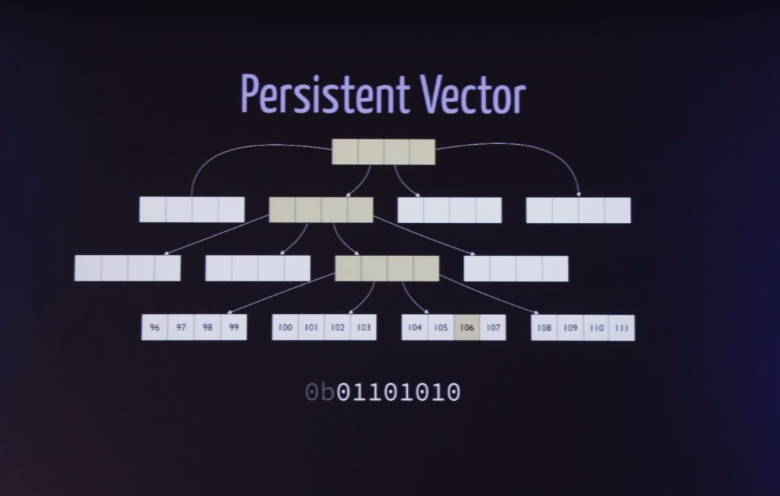

Now, a structure used in functional persistence looks like this:

David Nolen — Immutability, interactivity & JavaScript (FutureJS 2014)

David Nolen — Immutability, interactivity & JavaScript (FutureJS 2014)

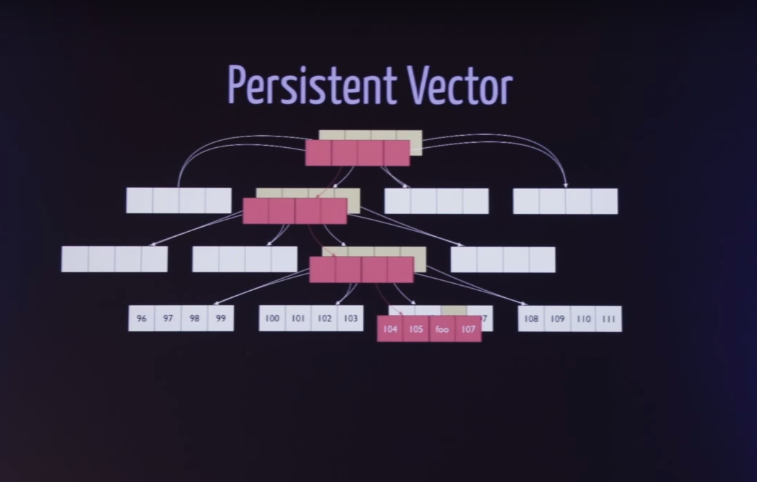

If we make a change, the references are simply updated:

David Nolen — Immutability, interactivity & JavaScript (FutureJS 2014)

David Nolen — Immutability, interactivity & JavaScript (FutureJS 2014)

These data structures are extremely efficient. We can create 34,359,738,368 objects with structural sharing.

I Want My Data Fast

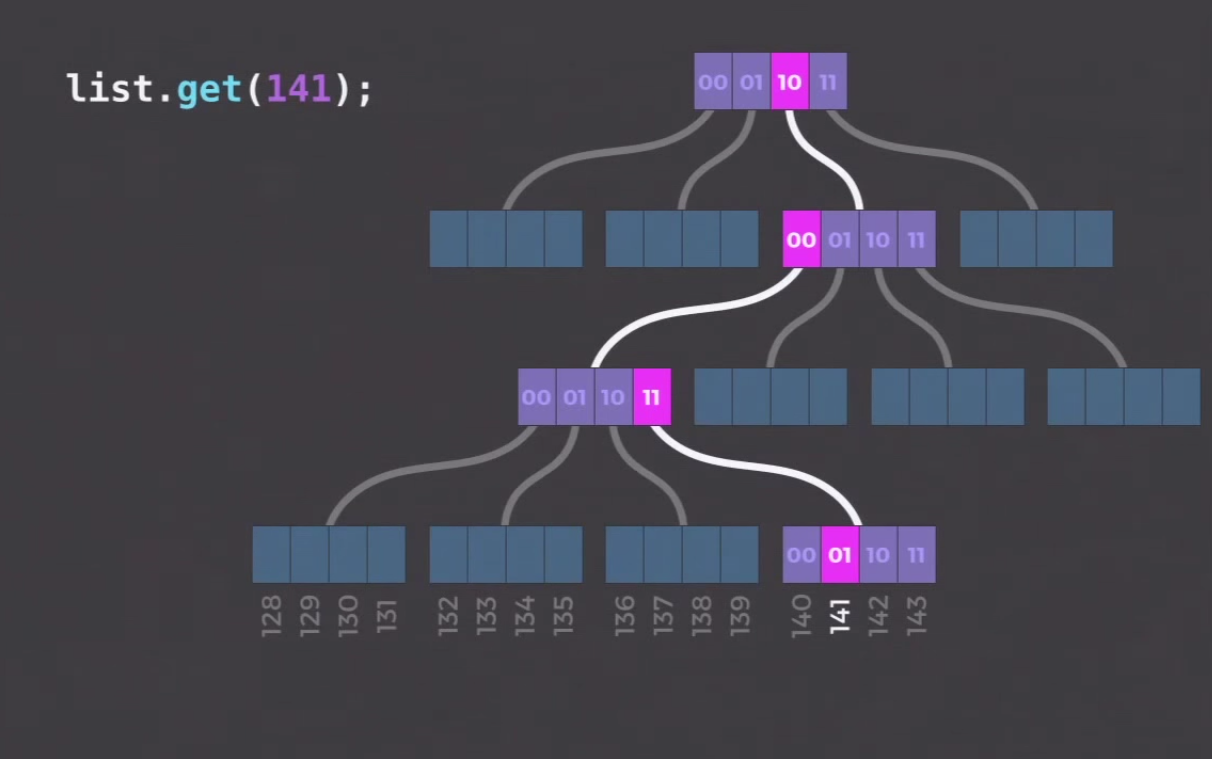

Accessing our data is extremely fast. When we look up a value, it’s expressed in its binary form and taken in pairs to search through the tree.

This way, you only need at most 7 lookups within the tree’s arrays to find any value.

React.js Conf 2015 — Immutable Data and React

React.js Conf 2015 — Immutable Data and React

This Sounds Complex to Use

While it’s somewhat complex in theory, this is available to us today. Libraries like React already use it. But most importantly, if we want to use it in our projects, we can use libraries like Immutable.

Immutable abstracts the complexity of these structures, giving us an API that lets us simply think in terms of List, Stack, Map, OrderedMap, Set, OrderedSet, and Record.

These are much simpler structures to work with.

The following examples are taken from the documentation.

We can pass objects to Immutable and then just think of them as values. The library gives us various methods to get values, iterate, compare, and much more.

We can compare values in simple ways.

var map1 = Immutable.Map({a:1, b:2, c:3});

var map2 = map1.set('b', 50);

map1.get('b'); *// 2

map2.get('b'); *// 50What’s Next

Personally, I believe immutability is a great characteristic we can leverage. Of course, immutable and mutable states both have their pros and cons, but it’s the responsibility of development teams to think about which path reduces the complexity of their projects.

I highly recommend reading the Immutable documentation, which is quite comprehensive. And if you’re already working on projects that use libraries like Redux, you can start using immutable state today.